“For the grass that you have just eaten, oh goat,

Give us some good pashm.

For the water that you have just drunk, oh goat,

Give us some good pashm.

Sit down on the grass and be still, oh goat,

So that we can take out your pashm.”

(A song the Changpa recite as they comb the pashm wool from their goats.)

Pashmina is considered the finest craftsmanship in the world which transforms the exceptionally warm and elegant Cashmere threads to opulent accessories. The fleece of Changthangi Goat is known as Pashm – The Soft Gold. This goat is exotic and is only found there, 15000 feet above sea level in Ladakh – Jammu and Kashmir, Tibet and some parts of China too, making the art of Pashmina even rarer all over the world.

Its all in the Process…

Pashmina is just a material, but what gives it the Royalty factor is Pashmina Shawl.

The Pashmina shawl must pass roughly 36 stages to reach the final shape where it becomes Useable.

The first step in the process consists in collecting the raw material from high altitude regions of Kashmir & Ladakh and as soon as summer sets in, the tribal people of Ladakh, Tibet and other parts of China go to the higher region to collect the same mostly on barter system. The raw wool thus collected is handed over to its collector-buyer in the hilly townships who pass it on to the traders in the Srinagar. The raw material is known as “Phumb-Wain”. While a big quantity of the raw material is collected in the Ladakh region, the bulk of it comes from Tibet and other parts of China via the mountain passes. The concerned traders in Srinagar sort it out according to grades and shades before fixing its price strand-wise.

Then comes the process of spinning Pashmina. The process begins with a sifting of rough hair from the soft material. The soft raw wool is stretched carefully, bit by bit, to complete the process known as “Puch Nawun”. The raw material is then rid of dirt and dust with the help of a 4 wide comb mounted on a foot wooden stand. This operation is known as “Absawun”. When the raw material is thoroughly combed and cleaned, it is then placed in an oval shaped engraved wooden trough (known as Tathal in the local language) roughly three feet long. Some quantity of broken rice is soaked in water for some time before it is coarsely powered with a stone pestle and sprinkled over the combed wool. The powder is known as “Khari Oat” and stone pestle as “Kajwath”. The wooden trough containing the combed wool mixed with rice powder is kept aside for three to four days. Though the wet rice powder emits a foul smell, it makes the raw wool whiter and softer. That is how the ancient treated the raw material and the practice is still in progress. Now it is time to comb the wool again more vigorously to ensure that it is perfectly clean, shedding every bit of the rice powder in the process. The raw material so cleaned is then made in the patty; like flakes locally known a “Thomb”. These oversized flakes are placed in an orderly manner in round tin boxes with lids. The material is now ready for spinning. The spinning wheel which is locally known as “Yander” is made of wood, it is three feet long with a wheel on its right side and a thin iron rod about a foot long called “Yander Tal” fixed in two grass spindles called “Kaun” in the local language on its left side. The iron rod (Yander Tal) is connected to the wheel with a piece of which serves as a beef. A piece of straw (known as “Sochne Tul” is mounted on the thin side of the iron rod and the yarn spun by is wound on it to facilitate its removal from the rod when each round of the spinning process is completed. Now, they hold a wool puff in their two left hand fingers supported by the thumb as the operation spinning begins with the turning of the wheel. While turning the wheel, the left arm goes up and down rhythmically without much effort to spin the delicate yarn. During spinning the delicate yarn gets cut a number of times but they restore it promptly. They repeat the exercise till they complete yielding a small quantity of the soft, delicate yarn.

The yarn mounted on a piece of straw is called a “Phamb Leeat”. Three or four such mounted straws are kept in a earthen bowl called “Kondul” marking the beginning of the second phase when it is turned and twisted on the wheel to make it foreplay and thus firm yet fine. So spun yarn is then mounted on a wooden spool known a “Prechh” wherefrom it is transferred on its edges. Locally it is known as “Yaeran Doul”. The yarn is called “Pun” (thread). A bunch of yarn is known as “Puyoe”. At this point, the buying pattern changes from weighing to counting.

Now begins the process of weaving. They sort out the spun stuff purchased by selling it to the weaver. The weaver in turn, sorts it out from the viewpoint of shade and fineness. Finally spun yarn is used as warp and the thick yarn as weft. The weaver then counts the stuff and weighs it too, before making entries in a register maintained for the purpose. The yarn is then put in a home-made starch which consists mainly boiled rice-water known as “Maya”. It stays like that for a couple of days in a copper bowl called “Dul” before it is spread out in sunshine to dry. The dried yarn is then untied and mounted on a wooden spoon known a “Preeh” and the process is known as “Tulun” which is generally completed in open spaces. Four to six iron rods about 4 feet in length are driven into the ground, at a shady spot by two persons working in opposite directions. This is the beginning of the process known as “Yerun” which is completed by “transferring the yarn from the “Preeh” with the help of smooth sticks. This is how the wrap is made ready for use. About 1200 threads arranged in the aforesaid manner is known as “Yaen” which suffices for making four to six shawls. The wrap is brushed and its broken threads rejoined (locally known as “Pen Kem”) before it is carefully mounted on the iron rods.

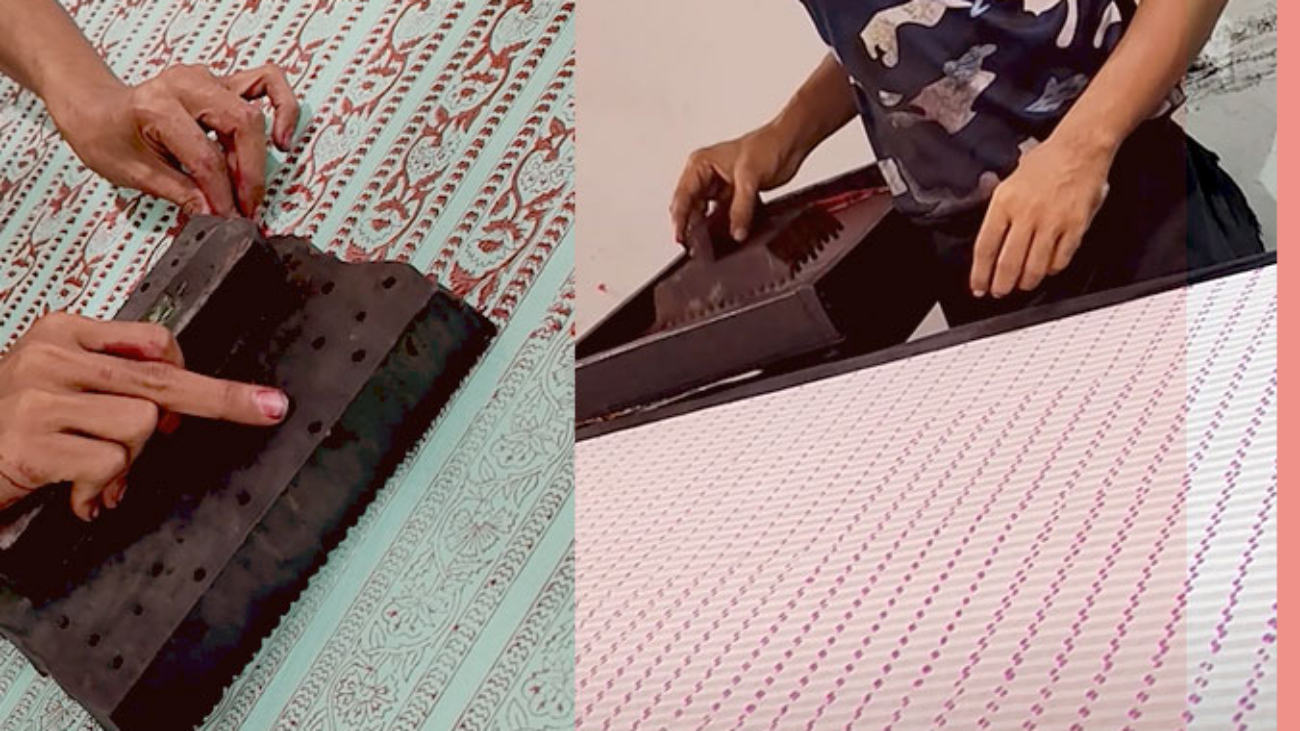

The last and the final process is Hand Embroidery. The hand embroidery/ sequin work is done by our skilled traditional artisans only.

After all this, the Pashmina Shawl is ready to be worn, cosily and beautifully!